Teaching English and looking for common language with Eritrean refugees.

This is a picture of my Saturday morning this week.

Because it’s not what you know but whom you know, I suddenly find myself teaching English to refugees. I have no qualifications, no experience, no expertise, but I do have a friend who has all those things. And who found herself looped into somebody else’s idea to start a Saturday morning free English learning program, and then she looped in some friends…and here I am.

I am humbled to tears, and divinely happy.

A few weeks ago, looking forward to attending class as an observer before being thrown in as a teacher, I got a call that a large family from Eritrea needed a ride. Mother, father, and eight children. Too many for one car. Or at least, too many when driven American style, where everyone is supposed to have a seat belt. I was acutely aware that we were dealing with a first world problem. In the Middle East, Africa, much of Asia, no one would bat an eye at pouring ten people into a Crown Victoria.

I have known only one other Eritrean, a woman I met in Saudi Arabia. She was astonishingly beautiful, the kind of beauty that makes you stop when you see her and wonder whether you’re in the right place.

This is where to find Eritrea:

This area where you find it is referred to as the Horn of Africa, for obvious reasons. If you get a little closer, you may notice that it’s a rough neighborhood.

According to what I learned from Wikipedia, Eritrea voted for independence from Ethiopia in 1993, and there have been no elections since. Human Rights Watch describes the Eritrean government’s human rights record as among the worst in the world. In June of this year, the UN Human Rights Council published a report accusing the Eritrean government of torture, extrajudicial executions, forced labor, rape, and sexual servitude. All Eritreans adults, 18-40, must participate in national service, including military service, but the terms of service are indefinite and often lengthy. Many attempt to flee the country, although they will be arrested if they are caught. Yet they still give themselves over to smugglers. If they’re lucky they make it to the Mediterranean and end up in overloaded boats headed to Europe. If they’re unlucky they’re caught in human trafficking on the way across Africa or the Sinai peninsula.

For some idea of what the stakes are, please queue up this episode of This American Life, in which a journalist responding to a tip finds herself on the phone with dozens of hostages pleading for rescue.

I don’t know the story of this family because we cannot yet communicate enough. On the Saturday morning I met them, I pulled up in front of a home that is a relic of Denver’s 1970s boom days, a weary-looking stuccoed split-level with cracks in the front steps, a front yard of dry dirt, and rattling wrought-iron banisters. The door was open, and children ran outside to greet us. Inside was a pair of secondhand sofas, a table, and a heavy-bottomed tube TV. They get to live in this home for free for six months, and then have to find housing they can pay for themselves. In a foreign country. In a language they don’t know and with an alphabet they can’t read. I have no idea how they are supposed to do that.

Zeru is the father, Mana the mother, and I was introduced to a swirl of children and teenagers with names I couldn’t understand or pronounce properly. Zeru insisted we sit. Mana insisted we eat. She disappeared into the kitchen and emerged with a platter of soft brown pancakes a foot in diameter stacked six inches high, which she placed on the table. Next came plates, onto which she ladled a scoop of stew. I tore off what I thought was a good-sized piece of flatbread to pick up the stew. She laughed, folded over the rest of the piece, and shoved it into my hand. Remember: ONE FOOT in diameter.

Yes, it was delicious. No, I didn’t need to eat anything else until dinner.

In class, a friend who would be one of my co-teachers started with introductions. “Hello. My name is Sharon. What is your name?” My friend extended her hand to me, and I answered. “My name is Margo.” She said it was nice to meet me, then moved to a couple of other English speakers before she addressed Zeru, who did a rather remarkable job of copying. Then to Mana. Then on around to the teenagers. We went through the letters of the English alphabet on a chart designed for children. Aa apple. Bb ball. Cc cat. We sang the alphabet song. We sang “Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes.” We sang the alphabet song again. (Boy, there sure are a lot of extra words in that song after you finish with Z.) We used pictures of common signs around town—CVS, DON’T WALK, STOP, WALMART—pointed to the letters, and asked the students to identify them. The gap between naming C and saying “Would you like fries with that?” seemed as wide as the ocean.

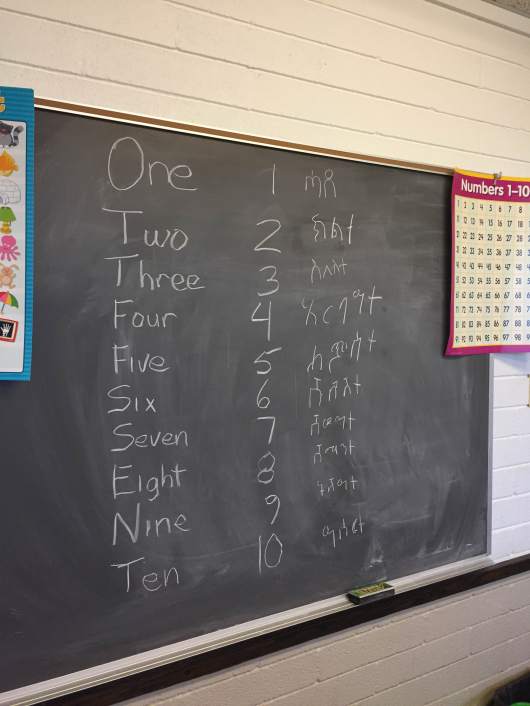

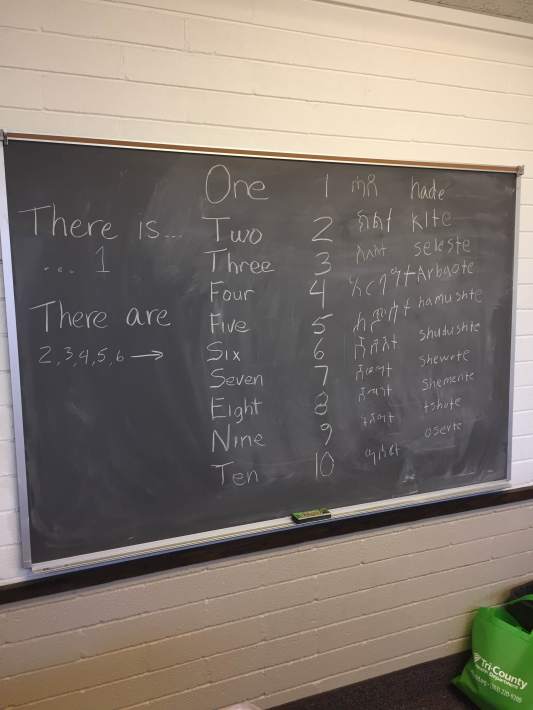

It has been three weeks, now. Today we went through numbers and their written-out names, and to help them label their own flash cards, asked them to write the names of the numbers in their own language. I believe it’s Tigrinya. Then, as I tried to write their words phonetically in English so I could repeat them back (my Tigrinya is HILARIOUS), Kidusun and Awet and Haptumariam—16-21-year-olds—jumped up and started doing it for me:

That’s right. They not only know the alphabet and the sounds our squiggles make, they know it well enough to translate their own language into English phonics.

You want to know how much Arabic script I’d figured out by the time I’d lived in Saudi Arabia for two years? Numbers. That’s right. Just the number symbols. And that’s only because they appeared on license plates with their Western equivalents directly below the Arabic ones.

I have not had to ask myself which way I would prefer to die. I have not wondered how to feed my children. I have not had to escape my home country, knowing I will probably never see it again. I have not had to leave everything familiar and embed myself in a completely foreign culture. I have not had to figure out how to buy food or find a job to support my family or find a place to live when I know next to nothing about my new home. And I have never been dependent on strangers who don’t speak my language to support me and understand me. I’ve never had to tunnel through a barricade of language that separates me from everyone around me, understanding that no one will ever dig toward me, and that if I am ever to survive in my new home it’s all up to me. But I am a human being, and can imagine it. And it buckles my knees.

So this is my homework. By next Saturday, so help me, I’m going to be able to count from one to ten in Tigrinya. Without looking. And know the numbers out of order. It seems like the least I can do.

My daughter’s best friend’s mom is from Eritrea. I had no idea of their history. Thank you for sharing this! Inspiring!

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

I had a bit of the same experience with Bosnian refugees while living in Albuquerque in the ’90’s. We are so sheltered, but we can use our stabile, peaceful situations to lift others out of what you have described–a nightmarish existence. It doesn’t take academic credentials. It only takes love.

LikeLike

They’d be a darn sight better off if I did have credentials, but at least the person providing the curriculum does!

LikeLike

To agree to go to Eritrea to teach English without any prior experience — wow, that’s just absolutely amazing and inspiring. Definitely looking forward to reading more about your time in Eritrea! 😊

LikeLike

Oh no! I’m sorry–don’t be inspired. I’m in the U.S., helping refugees resettled here. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always enjoy your stories Margo,

don’t worry about credentials… You are do a brilliant job !!!

Best wishes

Nowell

LikeLike

Thank you! I guess this makes me proof that with a willing heart ANYONE can help.

LikeLike

Interesting and a rare post on this country.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

welcome

LikeLike

Oops, I totally misread that haha! But still, helping refugees resettle in the US is impressive in itself too! 😁

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Hi,

I do have a CELTA certificate in English as a second language and can’t find any where to be put to use. I wish I could teach actual refugees. I sponsored two Bosnian families during that conflict. The first couple had a one month old baby when they came. This May I attended her wedding! It was one of the most satisfying things I have ever done in my life.

LikeLike

I can only imagine the joy of being able to attend that wedding. What a privilege! The group I’m helping started as a woman who sounds like you, determined to find a place to help, who just started calling family service charities, delivering meals, doing anything she could. Then she stumbled across someone else wondering what programs might be available for English learning…people who were looking for ways to help just started to cross each other’s paths. Perhaps you’re the one to start a new program where you are! 😉

LikeLike

Teach phonics

LikeLike

Yes indeed! I’m astonished at how quickly they’re getting it. If I understand properly, Zeru had only three years of school in Eritrea, and now needs to learn a second language when he probably wasn’t well educated in his first. I’m so impressed with their gritty determination to learn.

LikeLike

Loved this Margo. Ok if I forward it to all the volunteers? I think we all relate.

LikeLike

Yes indeed! And thank you for being the engine that keeps this car going. So grateful I’m in it. 😉

LikeLike

Alhamdulelah that people like you exist. Alhamdulelah for your great heart and open-mind. Alhamdulelah for you not being judgmental but rather humanist. I have being seriously upset lately by expats (or people dealing with foreigners back home) so you are like fresh air. Seriously.

LikeLike

Mashallah. You have touched my heart. Thank you.

LikeLike

Lovely writing, and a beautiful heart! I too had the privilege to teach and get to know a few Eritrean families, though not as newly arrived as the family you met – the kids had all already learned English in school, and it was only the parents who needed more language since they mostly spent their days working at the local poultry processing plant. As you say, it’s hard to imagine that transition. A couple men were working towards getting their CDLs. They had already driven large trucks before coming and had learned some English since arriving, but all that specialized vocabulary for the written test…! Such challenges. But some great connecting person-to-person and some fun memories as well.

LikeLike

Thank you! It’s certainly striking how much easier the adjustments are for children. I’m staggered to imagine how difficult it would be for me to exchange places with any immigrant.

LikeLike