Foreign hospital. It’s right up there with “foreign prison” on the list of places Americans don’t want to find themselves. Despite the way colossal screw-ups and failures happen as much in our own medical system as others, we continue to believe that when trouble hits abroad, you don’t want to be treated by anybody else.

It’s a noble, loyal sentiment. Very patriotic. Very endearing. Very impractical when you live abroad. A few months ago I figured out that years of various whiny complaints could be traced to my big toe, and calculated that the only way to not foul up any travel plans (perish the thought!) was to have a simple joint surgery here in Riyadh, the first minute we returned from Italy.

Reticence about foreign surgery is not unreasonable. Plenty of my expat friends–not just Americans–asked whether I felt safe. When possible, expats in Saudi Arabia do tend to put off elective healthcare until they can do it at home. But for a variety of boring reasons, that wasn’t going to work for me. And for heaven’s sake–it’s a toe. All in all, I’m really pleased with how everything went, but the despite the private hospital stacked with foreign doctors, the experience was still a distinctively Saudi one.

Now, let me be clear, the procedure itself went great. Very straightforward, clear-cut, clinical and smooth.

- Doctor, check. (UK citizen of African origin, with a Greek name, working in Saudi Arabia–my kind of guy.)

- Anesthesiologist, check. (Jordanian with a Canadian education.)

- Hospital, check. (Private, sparkly, full of Western-educated doctors and slick procedures. Five minutes after I checked in, as I was crossing the threshold of my room, I got a text giving me a username and the wifi password for the room. Nice.)

- Procedure, check. (With a spinal block, it was kinda like a really relaxing spa treatment and pedicure without the tickling and kicking.)

Outside the procedure, though, things took on that unique local flavor. First, the recovery room nurse, as she was apologizing about the crying children in there with me, explained that the boy on the other side of the curtain had just had his tonsils out, and (lowering her voice) that the doctor was telling the parents it would make him smarter.

The doctor. S-m-a-r-t-e-r.

(Turns out the Internet is full of pictures of puzzled babies.) The nurse told me that folks here believe tonsils are attached to the brain. And doctors (I choose to believe not all) find the best way to reassure parents that they’ve done the right thing in having them removed is to tell them what they want to hear. And you thought unlimited ice cream was a shabby promise.

(Turns out the Internet is full of pictures of puzzled babies.) The nurse told me that folks here believe tonsils are attached to the brain. And doctors (I choose to believe not all) find the best way to reassure parents that they’ve done the right thing in having them removed is to tell them what they want to hear. And you thought unlimited ice cream was a shabby promise.

Next, the patient room: It was was unlike any I’ve seen in the U.S. It had a front room, empty but for a 40″ flat screen TV and Saudi-style sofa wrapped around the perimeter on three sides. Sort of a bench with back cushions against the wall, like these:

Forgive me for not hobbling around to take my own pictures, but it’s a pretty typical Saudi arrangement. The one in my hospital room could probably hold 12-15 people (and entertain them). A short hall took you past the bathroom to the patient room, where you had the hospital bed and another L-shaped sofa for another 10-12 people. I, my foot, my stylin’ hospital gown, and my smudged mascara could have hosted 20-30 guests.

Forgive me for not hobbling around to take my own pictures, but it’s a pretty typical Saudi arrangement. The one in my hospital room could probably hold 12-15 people (and entertain them). A short hall took you past the bathroom to the patient room, where you had the hospital bed and another L-shaped sofa for another 10-12 people. I, my foot, my stylin’ hospital gown, and my smudged mascara could have hosted 20-30 guests.

And people seemed surprised that I wasn’t. (Though I know Americans are surprised I’m staying overnight at all. Me too. Roll with it.) I was asked a few times going into the procedure where my family was (“It’s a toe. He’s at work. He’ll come later.”), and at about 9:30 that night a woman came into the room to let me know the hospital closed at 11:00 and visitors would have to leave. She paused partway through her delivery as she noticed no one was there. “No family?” she asked, craning her black-draped head forward to make sure she wasn’t missing somebody lurking in the corner. I told her my husband had been here earlier, but that he’d gone home. Huh.

A Saudi hospital visit is a whole-family affair. Women wear abayas that often drag along the ground, bringing with them dirt from the street, sidewalk, home, the length of the hospital corridor where other abaya-draggers have been… Plus they bring food with them, giant platters of rice with lamb, goat, beef, camel (ahem), which are typically eaten communally off of plastic mats spread on the floor.

In fact, we made some jokey comment to one of the nurses about whether there’d been camels in the hallway, but she seemed baffled. Allowing for differences in cultural traditions of joking (she’s from the Philippines), we explained that it was because of, you know, MERS. Still nothing. Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome. I’m not sure at that point whether she was vaguely aware or just didn’t want to appear completely ignorant, but she gave some sign of recognition and said, “It comes from camels?” We explained that plenty of questions remained, but that the virus had existed in camels for a long time, and that virologists and epidemiologists weren’t sure yet how it was making the jump to humans, or whether camels were the sole carrier, but that there seemed to be a link. “Oh,” she said, shaking her head and straightening, clearly now in possession of all the information she needed. “They shouldn’t say anything until they know.”

Insert culture gap here.

Ah, and the food. My last full meal had been lunch the day before in the Paris airport, so, given that airport food is as notorious for awfulness as hospital food is, I couldn’t help but compare:

Ah, and the food. My last full meal had been lunch the day before in the Paris airport, so, given that airport food is as notorious for awfulness as hospital food is, I couldn’t help but compare:

A salad of spring greens, baby chickpeas, feta chese, radish shreds, arugula, and baby cucumbers, dashed with oregano and basil. A gruyere and bacon tart. (The crust was divine.) A dab of cheesecake from The Beloved’s tray. I rarely eat as well as I did at the self-serve on Concourse K at Charles DeGaulle Airport. (Nor do I pay as much. That part of the impression can be confirmed.)

A salad of spring greens, baby chickpeas, feta chese, radish shreds, arugula, and baby cucumbers, dashed with oregano and basil. A gruyere and bacon tart. (The crust was divine.) A dab of cheesecake from The Beloved’s tray. I rarely eat as well as I did at the self-serve on Concourse K at Charles DeGaulle Airport. (Nor do I pay as much. That part of the impression can be confirmed.)

Now, Arab Lunch at the Hospital, presented about 4:00pm, after I was deemed anesthesiologically cleared to eat:

Boiled brown meet of unknown origin (beef? lamb? I honestly couldn’t tell), tinted rice, flatbread, iceberg salad with a cup of vinegar, green sauce that didn’t make anything taste different, tangerine, laban (drinkable yogurt), vegetable soup, and the ubiquitous creme caramel (flan, only snottier). The tangerine was great. (Note: The rice, meat, salad, and roll are EXACTLY the same meal you get on every international flight on Saudi Airlines.)

Boiled brown meet of unknown origin (beef? lamb? I honestly couldn’t tell), tinted rice, flatbread, iceberg salad with a cup of vinegar, green sauce that didn’t make anything taste different, tangerine, laban (drinkable yogurt), vegetable soup, and the ubiquitous creme caramel (flan, only snottier). The tangerine was great. (Note: The rice, meat, salad, and roll are EXACTLY the same meal you get on every international flight on Saudi Airlines.)

Two hours later, dinner showed up:

Yup, second verse, same as the first, but with fish instead of brown animal, no laban, and a single crouton on the salad which now caused it to be labeled “Caesar.”

Yup, second verse, same as the first, but with fish instead of brown animal, no laban, and a single crouton on the salad which now caused it to be labeled “Caesar.”

Breakfast landed on my side-table a little before 7:00. Take it or leave it, folks. Again, brown flatbread, now with juice, coffee, a cup of hot water and a tea bag, and a plate with a big blue dome. Lift the dome, and…  A factory croissant. Starch your way to health! This came from “Diet Center,” and I learned yesterday of someone who’d purchased a month of food from them at staggering expense for her diet program. Nutrition is a young field around here.

A factory croissant. Starch your way to health! This came from “Diet Center,” and I learned yesterday of someone who’d purchased a month of food from them at staggering expense for her diet program. Nutrition is a young field around here.

Finally, checkout. The tricky part was coordinating checkout completion with the times Beloved was available to pick me up, and I had to do a lot of nagging to push the process along. Now make no mistake: I have been through PLENTY of this in American hospitals trying to get somebody out the door. There, the response is “We’re waiting for the doctor” or “Someone will be here soon.” Translation: “It’ll happen when it happens, sweetie. Your schedule means nothing.” Around here, the consistent response was “Inshallah it’ll be done.” For the uninitiated, “Inshallah” means “God willing.” In a practical sense, it means exactly the same thing: “It’ll happen when it happens, sweetie. Your schedule means nothing.” Except “Inshallah” emphasizes that it’s nobody’s fault.

In the U.S., blame-shifting is an art, and the tools are usually hierarchical structures. A customer-service worker isn’t the one who made the broken bike, the phone operator isn’t the one who messed up your hotel reservation. The boss has underperforming employees; underlings have an unreasonable boss. Talking to someone who’s actually responsible for causing your problem is nigh onto impossible.

In the Middle East, the blame-shifting is easier because the hierarchical structure is simpler: There’s us, and there’s God. And how DARE you challenge that one? I have to confess that “Inshallah,” as it’s used in Saudi Arabia, makes Westerners really, really, freaking crazy. It’s everywhere, a verbal filler used not too differently from the way an American might say “hopefully” or even “you know.” Inshallah your plumbing will work now. Inshallah your visa will come. Inshallah your refund will go through. Yes, it acknowledges that we little humans are kidding ourselves to think we have control of the universe. I absolutely get it, and agree it has its place in the cosmos. In allowing for unpredictable weather on the wedding day. In the randomness of an earthquake or a lightning strike. At stopping useless raging against things that can’t be changed.

But in the context of doing your own work properly, let’s be honest: it’s a cop-out. A way to slough off responsibility. The subtext is, “Why try?” It means, “It’s out of my hands, I’m not going to bother, I don’t have to think about it anymore. Whatever.” Double that when it comes from people who aren’t even Muslim. Then it means “I’m going to lay this on the surrounding culture because I’m not even a subscriber to the religious structure I’m invoking.”

(Those babies just keep giving.)

(Those babies just keep giving.)

God, apparently, did not will for me to go home at the promised time, and the (non-Muslim) nurses kept congratulating themselves during the morning that it was much better this way. Okay, I’m open to the possibility. Perhaps the God of Badly Done Paperwork saved me from the God of Traffic Accidents, and I’d be churlish and arrogant to say anything but “Thanks!” In either case, I’m home now, and now that the problem foot is out of the picture I get to don pretty shoes again.

Which I rank as a good outcome. But as I watch MERS researchers from the around the world puzzle about how the public health threat is being addressed in closed Saudi Arabia, I can get you at least this report:

- Rest assured, hospitals do not look like this:

No leeches, bleedings, unanesthetized amputations, or bottles of anything labeled “bitters.”

No leeches, bleedings, unanesthetized amputations, or bottles of anything labeled “bitters.” - Still, ignorance and superstition are barriers to getting correct information to the public.

- If something starts to spread from person to person, it’s hard to imagine better people for carrying it.

Or worse people for nourishing themselves so that they’re healthy enough to resist it.

Or worse people for nourishing themselves so that they’re healthy enough to resist it. - In a society full of expats, information doesn’t disseminate widely, and though healthcare workers all share English, they’re as disconnected from the national conversation as we all are.

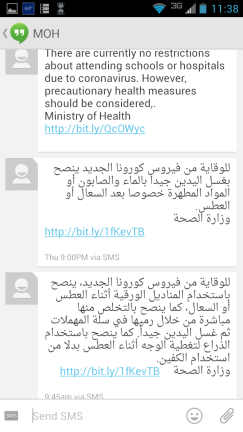

(This is the sum total of Ministry of Health information I’ve received about MERS. One text in both English and Arabic, one in only Arabic. I may be missing a thing or two.)

(This is the sum total of Ministry of Health information I’ve received about MERS. One text in both English and Arabic, one in only Arabic. I may be missing a thing or two.) - And finally, the global community is going to have to get used to leaving a lot of things in God’s hands.

Loved this post. Snottier flan. Puzzled babies. What was the deal with your toe?

LikeLike

I strained it during a long day walking on a 2″ heel, never took it seriously enough to rest, and five years later…arthritis. Had to clean out little bone spurs and rough spots. Lesson: If you hurt something that moves, deal with it! I’ve been walking weirdly around it for years and gave myself back pain & plantar fasciitis. Between that at the tennis elbow (probably partly connected too) I haven’t been able to exercise worth a darn in months. The Istanbul and Italy trips were all about pain management, so I’m VERY excited. Fingers crossed that I’m ready to play when I get home in June!

LikeLike